Main Scientific Contributions

Early Career: From Learnometrics to Learning Analytics

My initial research centered on the quantitative analysis of the production, discovery, consumption, and reuse of digital learning materials, a field I termed “Learnometrics” in my Ph.D. thesis (Ochoa, 2008). Being the first large-scale, in-the-wild quantitative studies on this topic, my work challenged the "Reusability Paradox" (Wiley et al., 2004), which suggested that smaller, decontextualized resources were more likely to be reused. By measuring reuse across varied materials (Ochoa & Duval, 2008), I showed that there is no inherent preference for smaller resources, with even large entities, such as complete courses, reused at similar rates. Using mathematical models with skewed statistical distributions, I further explained macro-scale behaviors in large repositories as reflections of individual author and consumer actions (Ochoa & Duval, 2009; Ochoa 2010, 2011b).

This early work led to my keynote at the first Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK) conference (Ochoa, 2011a), where I was drawn to Learning Analytics. My focus initially shifted to Curricular Analytics, analyzing students' academic records to understand behaviors, identify program bottlenecks, and assess program throughput. Using fuzzy clustering, exploratory factor analysis, sequence and process mining, and visualization techniques, I developed tools to analyze academic programs with only existing data. This work (Méndez et al., 2014) earned the Best Full Paper Award at the 2014 LAK conference.

Focusing on Multimodal Learning Analytics

While working in learning analytics, I noticed a "Streetlight Effect" (Freedman, 2010), where research focused narrowly on readily available online data, often neglecting valuable data from physical learning contexts. This insight led me to be one of the pioneers in the field of Multimodal Learning Analytics. I participated in and won the first Grand Challenge of MmLA (Oviatt et al., 2013), where our team used machine learning to predict student expertise in collaborative geometry problems based on multimodal signals (Ochoa et al., 2013). I extended this work by organizing and competing in the second Grand Challenge (Ochoa et al., 2014), developing models to predict presentation performance using multimodal features (Echeverría et al., 2014; Luzardo et al., 2014).

Under my direction, our team designed personal multimodal recording devices to give students control over their data (Domínguez et al., 2015) and proposed a framework to present this information to students and instructors (Ochoa, Chiluiza, et al., 2018). I authored MmLA chapters in both editions of the Handbook of Learning Analytics (Ochoa, 2017, 2022) and contributed to chapters in the ACM Handbook of Multimodal-Multisensor Interfaces (Oviatt et al., 2018) and Springer’s Machine Learning Paradigms (Chan et al., 2020). Additionally, I am a co-editor of Springer’s Handbook for Multimodal Learning Analytics (Giannakos et al., 2022).

MmLA to Support the Development of Transversal Skills: Oral Presentations and Collaboration

Once I developed the ability to analyze multimodal signals from learning activities, I sought to maximize the educational impact of this work. Providing timely, relevant feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007), which enables deliberate practice (Ericsson et al., 1993), is essential for developing transversal skills like communication, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking (Griffin & Care, 2015), but it remains challenging for instructors to offer detailed, regular feedback in larger classrooms.

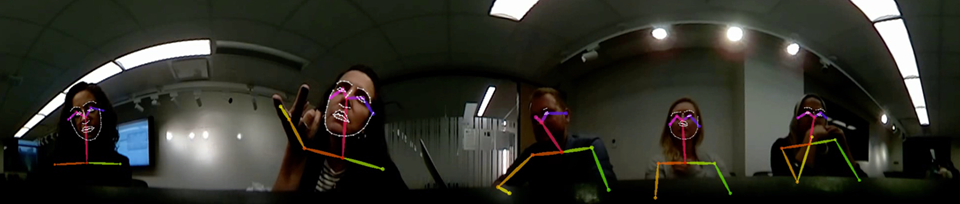

I saw an opportunity for MmLA to enhance both instructors' capacity to provide frequent, constructive feedback and students' ability to act on it effectively. To start, I focused on communication skills and developed a prototype tool that records presentations and provides automated feedback on aspects such as gaze direction, posture, speech volume, filled pauses, and slide design. This tool, validated with 83 students (Ochoa, Domínguez, et al., 2018), demonstrated over 80% accuracy in feature extraction, and students found the feedback useful. Recognizing the need for broader implementation, we scaled the tool for use in large courses. In collaboration with faculty from Physics and Communication, we ran studies with 1,099 engineering students, showing significant improvement in specific communication sub-skills, particularly among those with initially lower scores (Dominguez et al., 2021). To date, this remains the largest MmLA implementation. We further tested its effects in a controlled experiment with 180 students, finding a small but meaningful improvement in presentation scores (Cohen’s d=0.25) in the group receiving automated feedback (Ochoa & Dominguez, 2020). To support the growth of this research area, I also conducted a comprehensive review of automated feedback tools for oral presentations (Ochoa, 2022) and studied and released OpenOPAF, an open-source system designed to support easy adoption and contextual adaptation (Ochoa & Zhao, 2024).

In parallel, my research group at NYU and I explored MmLA for collaboration skills. Given the limited effectiveness of existing Collaboration Learning Analytics (CLA) tools (Ochoa et al., 2024"), we began by analyzing current limitations and proposing theory-based, pedagogically-sound frameworks to improve CLA tool design (Boothe et al., 2021, 2022; Huang & Ochoa, in print). We developed low-cost multimodal sensors to capture collaboration in both in-person and remote settings and deployed them in Biochemistry recitation sessions, where they tracked students’ collaborative behaviors. Working with instructors, we used these observations to inform activity redesigns and improve instructor-student interactions (Lewis et al., 2023).

When the COVID-19 pandemic limited in-person research, we examined the impact of online participation feedback through a semester-long study with 156 engineering students across six courses. Although students understood the feedback, it produced minimal behavioral changes (Ochoa et al., 2023). To better understand this result—common across CLA tool studies—we conducted a controlled lab experiment with 56 participants across 15 groups, revealing cognitive and metacognitive decisions that drive students’ responses to feedback (Ochoa et al., 2024). These findings are now guiding a more cognitively focused approach to designing CLA tools, which we are actively testing in ongoing experiments.